After lifting up a shout of praise, the introit for Holy Mass exults, “Quam terribília sunt ópera tua, Dómine!/ How terrible are thy works, O Lord!”

The English language has the disconcerting habit of changing itself entirely as it drifts through the generations. Teenagers in particular are accomplished verbal pugilists who batter the poor dictionary into submission. The process occurs rapidly. I’m not only unable to read Beowulf in its original English because it has changed so much, but, as a middle-aged man, I can no longer even understand what people under the age of 30 are saying half the time. If you text me, your words had better be grammatically correct full sentences or you won’t be receiving a response. Emojis will get your phone number banned from my address book.

The evolution of words is unceasing and the word from our introit, “terrible,” is a great example. In Latin, it means to excite fear but, again with “fear,” we have a distinction to make, because fear is a two-edged sword meaning both to be afraid but also an admiring respect. For instance, I might say that I fear the power of a cyclone, meaning I respect its power and beauty and am afraid of it at the same time. This is what it means to fear God, to stand in awe of his majesty, understanding that he can unmake me at any moment he so pleases. “Terrible” is also a two-edged sword. To say that God’s works are terrible does not mean they are monstrous or bad. My English teacher in school might have written that my essay was a terrible effort but he didn’t mean the same thing as the Psalmist, who means that God is the principle of life and his works are beyond our imagining. In modern English, those two aspects of the word terrible have split apart. You can hear it when you compare the word “terrible,” to the word, “terrific.”

God’s works are terrible. His love is terrible. His love is dangerous. He will take your heart. He wants all of you, which is why the poet George Herbert who also happened to be an Anglican pastor, expresses caution when he writes, “Love bade me welcome. Yet my soul drew back.” Loving God is an existential risk. What a fearful thing, to hand ourselves into the keeping of the Almighty. In order to do so, we must have a certain amount of trust, that God is who he says he is and we can place our heart in his hands. He won’t break it.

Now, when we describe God’s love as dangerous, we must be careful to distinguish it from sin, which is also a dangerous love. Here’s the difference. Sin begins in pleasure and brings us into danger, but God’s love begins in danger and brings us into safety. God’s love is dangerous at the outset but, if we give ourselves to him, it forms a bond stronger than death. It is our salvation.

God’s love leads us to ourselves whereas the love of sin leads us out of ourselves. This is why St. Paul says, “I beseech you as strangers and pilgrims to refrain from carnal desires which war against the soul.” He’s speaking of sin which alienates us from our own selves and stops our attempts at achieving our potential dead in our tracks. Sin is a twisted, inverted approximation of love that obliterates the object of its desire through disordered attachment, and unfortunately the object that a sinner loves so much is the sinner himself.

St. Paul also says that others may, “by the good works which they shall behold in you, glorify God in the day of visitation.” In other words, God’s glory, the visible expression of his dangerous love, a sacred light that blinds those foolhardy enough to stare directly at it, is strong enough to shine in a mediated fashion even through you and me, sinners though we are, we glow and the world will behold the love of God through us. We are, in this sense, temples, the residence of the terrible sacred.

This, to me, is immensely convicting. I think of how casually I stomp and rumble through life. The thoughtless ways I speak, how I move through the world numb to the great romance that calls me onwards, my mumbled, hurried prayers, my lazy attitude towards spiritual development, the sins I so casually commit because I know I can go to confession later. It’s a love grown lukewarm, a temple falling to ruins, and it is not how I desire to live. I want to jump into the furnace with both feet, for divine love to burn hotter and hotter within my soul, to blaze like incense before the altar of my God, from a stony charcoal to a star.

Or, at the risk of mixing metaphors, right now in the springtime we can watch the flowers open their petals from the buds, many of which set over the winter. I have a huge magnolia tree that blossoms in thousands of pinkish-white, translucent flowers that for all the world look like the tree is lit by a white flame. Each year this tree bides its time all through winter, setting the buds, and manages a display of grandeur that I almost don’t understand how it exists. I know how it happens but the meaning of it pulls me up into another world. Each year I half-expect it won’t be able to pull off the finery again, but it does, and every time I sit under it I’m reminded of, believe it or not, a poem in which Rainer Maria Rilke writes, “Look, we don’t love like flowers with only one season behind us; when we love, a sap older than memory rises in our arms.” It’s a love, an endless divine love, stored up like an inheritance, an ancient blessing so spacious that we can travel as far as we wish without having to step outside it.

It rises from the earth ceaselessly, striving towards Heaven. It is a love without end. It is vestal and immaculate, that is, secret and hidden until it reaches out for us. It goes forth and yet does not leave its native depths. It appears but cannot be caught. We get hints of how terrible it is in the paradoxical, poetic nature of Our Lord’s teaching and the embodied beauty of the liturgy. It’s why we make the liturgy solemn. We ritualize it and are oh so careful. We are stirring up the embers of a fire we cannot directly touch.

You shall not see me and you shall see me, says Our Lord. Death is birth. Sorrow is rejoicing. Suffering is joy. The Cross is victory, and the love of Christ conveys his best gift that no one can take from you. It’s not a safe gift. It’s not tame. He trusts you and would give you everything. This is what Our Lord tells his disciples, tht his love does not originate in this world and, even as it is immanent, it remains transcendent. It’s a frightful love we cannot control. We can only accept it and, if we dare, return it.

When I was younger, at the outset of discovering my vocation and trying to chart my future, I had all these dreams of doing great works, of being influential and admired. But, at this point I don’t really care if I walk on water anymore, I’d rather just throw myself in and try to swim to shore, because that’s where my Lord is. Is it dangerous to jump off the prow of a ship into the ocean and swim for your life? Yes, absolutely, but love doesn’t just sit there like some object, it has to be made and nurtured and risked. It is fed with the countless actions of a lifetime, our self gift.

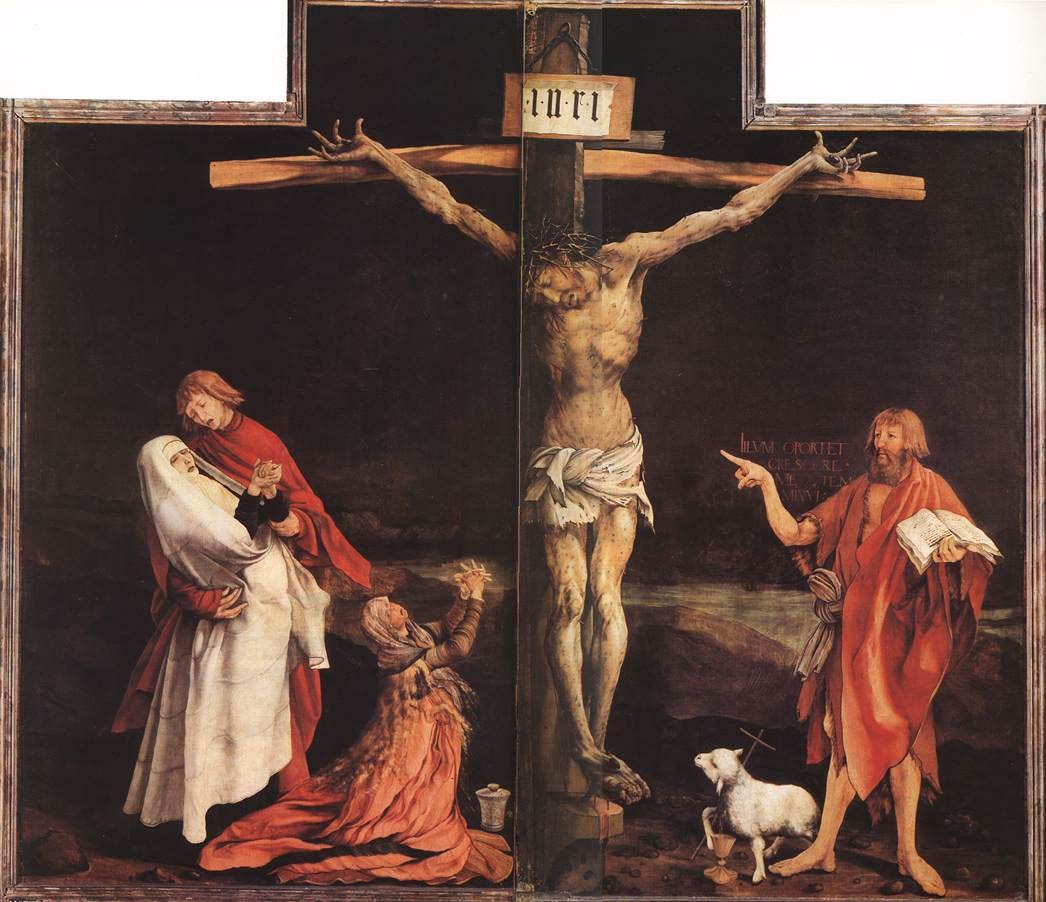

Our Lord is there, in the danger, waiting to meet us. Because remember that his love is first of all dangerous to himself. It takes him to the Cross. And there, he risks everything for us, even knowing that we might not accept his sacrifice. And this is his most terrible work – the Cross, the redemption of mankind. It has no limits, this redemptive grace. Accept it, every single day, return it every single day, and it will save you.