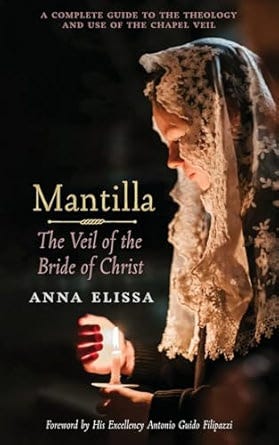

Because of the cultural baggage, the topic of women veiling their heads at Church is not well understood. So, because I don’t have a Sunday homily today, my original plan was to offer in its place a short book recommendation on veiling. The book in question is Mantilla: The Veil of the Bride of Christ by Anna Elissa, which was graciously sent to me by Os Justi Press.

I received the book. I read it. I found it to be thoroughly researched and clearly written. Anna Elissa gives an easy-to-read description of the history of the chapel veil along with some its theological import. She also provides practical tips and offers a number of testimonies from women who veil for Holy Mass. For a woman who has never worn one before, the whole process can be intimidating and there’s a certain reticence to stand out if you’re in a parish where veiling isn’t the norm. Anna Elissa does a great job in countering that reticence by providing good information and plenty of encouragement, particularly on how the veil has assisted in the development of the spiritual life of many women who have begun wearing one.

So, if you’re looking for a good book on this topic, I recommend this one.

Now, I have additional thoughts. Lots of them.

If you’re interested in a sustained reflection on why we veil the sacred, how a poetic image functions as a veil, and why poetic images are absolutely necessary if we desire to connect to the transcendent, read on. Fair warning, though, this one is more dense than my usual homiletic fare, and it’s more of a wandering exploration rather than a tightly knit essay.

Let’s start with some of the traditional (and quite convincing) reasons women veil at Holy Mass.

One of the first reasons given for veiling is modesty. Anna Elissa covers this topic quite well so I’m going to content myself with the simple observation that modesty reveals as much as it conceals. We dress modestly not simply to avoid objectifying the body or turning it into an occasion of sinful lust, but also for a positive reason, to adorn the human form so as to reveal its nobility. This is why modest dress emphasizes the harmony, gracefulness, and elegance of the human person. It isn’t necessarily modest to drape a giant burlap sack over yourself and cut out two eye-holes. It is, however, modest for a woman to wear a graceful, dignified, feminine dress or a man to wear a suit and tie. Clothing, in this regard, is a revelation that the body is meant for redemption. The resurrection is bodily. The veil, as a modest article of clothing, is a manifestation and anticipation of bodily glory. Specifically the feminine glory of Mother Church redeemed.

Secondly, if clothing, modestly worn, reveals specifically feminine or masculine perfections, then it follows that veiling is a recognition of the difference in the sexes. Man is submissive to God and woman is submissive to her husband. The sexes are distinguished hierarchically.

Further, the lower creatures over which we have stewardship are also created to fit into hierarchical relationship. When creatures find their proper place and order, they begin to reflect God. The cosmos is meant to function as a mirror, or icon, of the divine. Creation is a poetic image (both overall and in the myriad images that comprise it). We glimpse God’s Goodness in the goodness around us. His Beauty in beauty. And so on. Creation, in its goodness and beauty yet undamaged by sin, participates in a higher order. That higher order remains always itself and our lower order remains always itself but, by the miracle of the poetic image, which is a veil to conceal and reveal, an analogical relationship is formed by which God makes himself present through created things. He allows us to participate in his nature by adoptive grace. This hierarchical order is precisely what is acknowledged and praised by the custom of women veiling. The veil is one, extremely literal, example of a poetic image.

Thomas Howard comments, “The threshold between the commonplace in our world...and the remote regions of felicity turns out to be very low.” In other words, the veil isn’t meant to be impenetrable. God greatly desires to arrive to us in beauty. He seeks us out. To paraphrase Simone Weil, he is wearing himself out, even to his own destruction on the Cross, to push through the veil and make his way to us.

Christ moves Heaven and earth to reveal his glory to us and draw us into his inner life. It really isn’t that much to ask that we attend, in our own small way, towards meeting that divine love. All that is required is to slow down, pay attention, and engage in the little things (like dressing nicely, working towards beautiful liturgy, taking veiling seriously, and so on). If we desire to cross the threshold of felicity and embrace the ancient and ever-fresh beauty of Christ, it isn’t difficult, but we must be willing to make the effort and recognize that it is the poetic image alone, the aesthetic, that makes the connection possible. We cannot peer through the veil via abstract intellect. We only arrive to the universals through the particulars. There are no shortcuts. As John of Damascus teaches, “image is everywhere a figure of immanence.” The poetic image closes the distance. In terms of women veiling, the literal physical act of wearing one makes a woman feel her feminine value, to inhabit it.

This intimate dwelling in the reality that enfolds the appearances is enabled by the aesthetic power of the poetic image and is, in fact, is why we veil absolutely everything that is sacred. We veil Holy Mass in a multiplicity of ways. The tabernacle, chalice, ciboria, altar, and priest are veiled with vestments. The altar is veiled by incense. The prayers, addressed primarily to God the Father, are offered under the veil of a sacred language (an ecclesiastical, stylized form of Latin), and the Eucharistic Host is veiled under the appearances of bread and wine.

Women are included in this veiling of the sacred.

Simply because we recognize a hierarchical structure in the sexes does not imply the lower is less valuable than the higher. In fact, in the upside-down economy of the Kingdom, the lower is actually higher. Our Lady makes this point poetically in her Magnificat; “God has lifted up the lowly.” But we’ll leave this aside as a digression because we also acknowledge that, in terms of our common humanity, the lower is where we all begin, both men and women. Poetic metaphors frequently overlap because their logic is nested and layered (Picture St. John walking around and around the walls of the New Jerusalem in his apocalyptic vision, examining the jewels, the facets, the angles, trying to poetically describe a reality only he is privy to seeing, and he finally resorts to a profusion of overlapping imagery). Men, masculine though they may be, are nevertheless members of the Church which is Mother. As such, they are integrally connected to her (the Church is both Bride and Mother; again, overlapping metaphors), and receive everything they have from her hand. A man always remains connected to his Mother. It is she who sets him off on his fatherly vocation. Christ is the sole Savior and source of grace but, in his wisdom, he asks his Mother to mediate those graces. He asks her, essentially, to make her life and person a poetic image, a mystical ladder connecting the lower and higher. She is, in a manner of speaking, a maternal veil (I’ll have a lot more to say on this topic in my book on the Poetics of Our Lady, which will be published by Angelico Press in Spring 2026).

Following on all of the above, we can declare quite confidently that the feminine is sacred. Motherhood is sacred. As so many poetic images and veils, any individual woman at prayer is an image of the universal Church herself at prayer. Women are living expressions of creativity and cooperation with God in the making of new life. Motherhood at prayer is prophetic, and the feminine reaches more deeply into the truth than anything else, to such an extent that they become the veil through which all other images are reborn. Thus, women veil and participate in the reality of their vocation to the mediation of new life, first into this world and then into the next.

Again, the physical veil itself is irreplaceable. It is a specific, concrete poetic action that cannot be merely converted into an abstract principle and then discarded. The universal and the individual are entirely empathetic with each other, completely participatory. I say this because we might agree with all of the above but still insist that women veiling at Holy Mass, particularly in our modern era, ought to be a matter of the heart only. Modesty and sexual difference and expressions of the sacred ought not be belabored in our parishes to such an extent by formal expectations and exterior displays. It’s too much. It’s over the top. It’s, dare I say it, old-fashioned and embarrassing.

I must point out, here, that this same argument would be adhered to, for instance, by the iconoclasts, who argued that sacred images are nothing more than idols distracting us from the spiritual worship of the true and invisible God. In the same way, a modern person might argue that veils on women (and all the other veils employed in sacred worship) are at best a distraction and at worst the misguided worship of exterior forms. Churches (and life in general) need to be less fancy, vestments more plain, the altar and music less adorned, and women unveiled. True worship of God, under these premises, is abstract and intellectualized, a claim that indisputably defines the practical approach, as illustrated by a typical, chatty priest who explains the hidden glory of modern-day, relevant and unadorned liturgies if we would only just listen to him and educate ourselves enough to understand, as if the problem with bland liturgies is the fault of the laity’s lack of intellect. Homiletics and ongoing explanations take center stage, having essentially abstracted and replaced the older poetic symbols that imparted knowledge through the aesthetic imagination.

Of course, the argument can inexorably be pressed forward even further – why receive the Blessed Sacrament at all? Why not simply believe in our hearts and receive Christ spiritually? Thus enter the protestants and the spiritual-but-not-religious and those who worship the god of their making in their hearts alone. Thus enter the cultural iconoclasts, the pajama-wearers at the grocery store, the cult of the casual, the flattening out of all interior beauties into the surface appearance alone. Thus re-enters idolatry.

I use the example of the iconoclasts quite intentionally because the example makes clear that objections to veiling the sacred is a rejection, generally speaking, of the poetic image. It places sacramentality itself in question and is essentially a Christological heresy. St. Theodore teaches as much, writing that the iconoclasts deny an essential element of Christ's human nature, amounting to a denial of the reality and physicality of the Incarnation.

Thomas Pfau, in his book on the poetic image, discusses the iconoclasts’ issues with Chalcedon, summarizing; “Ultimately, what causes the iconoclasts’ polemic to go astray is their failure to distinguish between physical matter and Christ’s living form.” (181)

Owen Barfield, coming at it from another angle, argues that if we deny that the phenomena around us (created things, poetic images, art, and so on) are doorways to the transcendent, then we are become idolaters. We are worshiping appearances and not seeking the truth of the deeper, connected reality (because we’ve denied that there even is a deeper reality), thus disconnecting the spiritual life from physical existence. Under such a belief system, what happens to the Incarnation? It would be an impossibility.

No, we must admit of the veiled sacred, that we are made in the image of Christ, destined for a greater reality, and our visible bodily existence participates in invisible spiritual existence. The two are intertwined and cannot be disconnected. The Incarnation is a true assumption of human flesh by which the physical is united to the spiritual. It instigates the redemption of the physical world which is, even now, being drawn into the higher reality via the suffering, immolated, resurrected, and ascended Body of Christ.

We are, right now, in the presence of the veiled sacred. Remember, the veil conceals and reveals. It makes distinctions. It occupies an analogical, connective space. The veil is absolutely necessary because, although God’s glory is breaking into our world and the invisible is being made visible, we are not yet ready to look directly at the reality. Everything must be mediated by our senses. Grace is mediated by our Mother. She provides ritual, beauty, sacramentality, and liturgy, which are poetic veils keeping the divine light from blinding us (destroying us, even). By doing so, the veils allow us to actually look and behold that which we’re capable of seeing. Our Lady is the Moon reflecting the light of the Sun, a light which we would never dare to apprehend directly.

If we wish to catch a glimpse of God’s glory, we must have veils. Or we see nothing.

The objection still lingers; why a literal veil worn by a literal woman? Can’t we move on from such overwrought, poetic symbolism?

No we cannot.

Here’s why. Unveiling is an apocalypse. It is the entrance into unmediated knowledge of the object, grasping the essence of it, even unfolding into unity (The Beatific Vision, for instance, is an unveiled contemplative look that results in unity with God and adoption into the divine life of the Trinity). This unveiled sight will be a blessing beyond comprehension, but we are not yet ready for it. The veil between us and the Beatific Vision is not an abstract concept. It’s a matter of life and death, a physical limitation written into creation for our good.

We know God through our senses and do not possess direct intellectual knowledge of him in the manner of the angels. Human beings are analogical. We are animal bodies with an intellect that can hold abstract concepts of eternal significance. By forming mental concepts, we bring time into eternity. But we cannot accomplish this if we never live in time, if we never interact with real, existing things. The veiled image is required if we ever wish to acquire knowledge deeper than the surface level. As Dionysius says, “It is quite impossible that we humans should, in any immaterial way, rise up to imitate and to contemplate the heavenly hierarchies without the aid of those material means capable of guiding us as our nature requires. Hence, any thinking person realizes that the appearances of beauty are signs of an invisible loveliness.”

The veil manifests transcendence into the visible world as a sign of glory, but also represents the gathering up of each individual woman who wears one into the unity of the universal Church. It is absolutely necessary as a form of aesthetic knowledge, which is a manner of knowing that is not reducible to abstract concepts. The image is a manifest presence of a truth lying just beyond our senses, one which we receive dynamically and with active engagement. The beauty of it calls to us and bids us forth. Without poetic images, we know nothing. We languish.

Without literal, physical veils we lose sight of the sacred. This is why a phenomenological examination of women veiling at Holy Mass is so fruitful (which is simply a fancy way of saying that the best way to understand veiling is to ponder how the veil has a deeper significance, how the surface level appearance is connected to a spiritual reality). Along with other literal veils of the sacred in the liturgy, the veils women wear explain the meaning and necessity of poetic images but also remember that the veils themselves when made visible as they are when worn by women also are poetic images.

A veiled woman at Holy Mass is a poetic image that explains all other poetic images.

A poetic image operates as a threshold. It is transformative as it draws the visible, surface-level appearances right up to the boundary of the invisible sacred. The image transfigures before our astonished eyes. St. Paul is clear that the image is able to accomplish this same transformation in us when he compares the spiritual life to looking in a hazy mirror. The mirror both conceals and reveals, and our method of making progress in the interior life is to keep looking for whatever reflections of the divine we might be able to glimpse. In contemplating the veiled image, we ourselves transform into the image we behold, the image of Christ towards which we strive. A woman who veils at Holy Mass is acknowledging that we are standing before the mirror. She becomes more herself.

A woman veiled is empowered. Like Our Lady, she assists her Son by taking on the aspect of mirror and source of knowledge of the divine. A woman who veils at Holy Mass benefits the entire Church because she mediates poetic knowledge not only of the feminine and motherhood but also Christ, a knowledge that can only be discovered in her willingness to conceal and reveal, to become a poetic image.

We might argue that woman are imperfect. They are not Our Lady. In the same manner, men are imperfect and we ought to tone down our emphasis on his iconographic role as father and priest. If they are poetic images, they are so imperfect as to be useless. Better to jettison all that nonsense and go straight to the pure, intellectual knowledge, but Pfau writes, “the icon’s aim is not to produce a verifiable representation but to induce in its beholder either a state of focused remembrance or a similarly concentrated, prayerlike attention to an invisible, spiritual presence…” In other words, veils remind us who we are. Yes, the veil is by definition imperfect (thus the struggle of all poets and musicians to say precisely what they mean), and falls short of the reality. But this is precisely the point. The veil is hope. The veil is a promise.

Maybe I take all this stuff too seriously. Maybe I’ve fallen so deeply into the depths of phenomenological poetics that I can no longer think straight (as if I ever could). All I know is that a book like Anna Elissa’s is full of personal testimony from woman after woman for whom veiling changed their entire experience of femininity and prayer, for whom veiling unlocked the inner meaning of Holy Mass. All I know is that when I myself encountered the poetics of Holy Mass by stumbling into a liturgy that earnestly sought the fullness of beauty, it changed my entire spiritual life. Before that, I was over-intellectualized, depressed, and struggling with basic theological concepts and virtues. I could see nothing of the God I so desperately wanted to believe in.

When I finally discovered the Traditional Latin Mass of the Catholic Church, everything about the liturgy was veiled. Finally, I knew, here was a mirror to the sacred. I could let my guard down. Finally, a religion that takes the mystery of our creation and destiny seriously enough to hide its blinding light from full view. I could stop fretting about my lack of intellectual understanding and rest in ancient beauty. Finally, a poetic world that truly mediates transcendence. I didn’t understand it, but something in my soul shifted. Through the veil God revealed the hem of his garment.

Father, your deep dive into the poetic/artistic light of the mantilla is so important. As one chamber of the four parts of the True Catholic 'heart' we need to dwell there for a time and then move as guided by the Spirit to consider the other three in God's time. The four chambers are the Mystic (M), the Artistic (A), the Scientific (S) and the Theologic (T).

MAST, a pole raised up is a potent image for a ship (Barque?). It is essential for movement (Sails), identification (Banners) and communication (Antenna).

Jesus speaks to the source, center and summit of this Truth when he says "when I am lifted up I draw all men to myself."

As a noetic for our Christian journey of faith MAST keeps us focused on why secular and specialized worldviews are incapable of transmitting this Fullness of Truth.

ANNUNCIATION

(John Donne)

Salvation to all that will is nigh;

That All, which always is all everywhere,

Which cannot sin, and yet all sins must bear,

Which cannot die, yet cannot choose but die,

Lo! faithful Virgin, yields Himself to lie

In prison, in thy womb; and though He there

Can take no sin, nor thou give, yet He’ll wear,

Taken from thence, flesh, which death’s force may try.

Ere by the spheres time was created thou

Wast in His mind, who is thy Son, and Brother;

Whom thou conceivest, conceived; yea, thou art now

Thy Maker's maker, and thy Father's mother,

Thou hast light in dark, and shutt’st in little room

Immensity, cloister’d in thy dear womb.

______________________________

The ARTISTIC LIGHT of Ste. Jeanne d'Arc, her testimony:

https://www.jeanne-darc.info/biography/banner

______________________________

I wrote this poem maybe 15 years ago to describe what I believe is at stake if we do not champion this fully integrated approach. With AI's ascendency, we are fast running out of time.

DRAWN AND QUARTERED

by Mike Rizzio

Four chambers, but one purpose,

Four Gospels live to tell,

A Sacred Heart, so wounded,

A lance launched straight from hell.

Our brokenness, bloodletting,

True Mystics judged insane,

King Science, throne ascending,

To deaden all our pain.

Four riders, on four horses,

Steeds rearing for a treat,

Our corpse, nears rigor mortis,

For Art not Science meet.

But wait...a ray of His Glorious Sonshine...

One part—sacred theology,

One part—mystic sight,

One part—true science,

One part—creative light.

...and if ever two lungs breathed forth,

East-West, air that is sweet,

Aloft they'll send His Body,

Heartbeat, Heartbeat, Heartbeat.

"wandering exploration instead of a tightly knit essay". Can you just write a syllogism and save us all some time?